Share

The Africa File provides regular analysis and assessments of major developments regarding state and nonstate actors’ activities in Africa that undermine regional stability and threaten US personnel and interests.

Editor’s Note: The Critical Threats Project at the American Enterprise Institute publishes these updates with support from the Institute for the Study of War.

Key Takeaway: Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed met with Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) leader Abdel Fattah al Burhan in Sudan in early July as Sudan’s civil war has moved closer to Ethiopia’s border, which risks destabilizing already turbulent areas of Ethiopia. The timing of the visit highlights Ethiopia’s concern that the Rapid Support Forces’ ongoing offensive against the SAF near Sudan’s border with Ethiopia could stoke ethnic tensions in Ethiopia’s Amhara and Tigray regions and benefit ethno-nationalist militants that are hostile to the Ethiopian government. Ethiopia is also well-connected to the other stakeholders in Sudan’s civil war and is trying to advance multilateral, African-led peace initiatives to stabilize the situation.

Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed met with Sudanese Armed Forces leader Abdel Fattah al Burhan in Sudan in early July as Sudan’s civil war has moved closer to Ethiopia’s border, which risks destabilizing already turbulent areas of Ethiopia. Abiy and Burhan said they discussed Sudan’s ongoing civil war and potential peace solutions during their meeting in Port Sudan but did not publicly clarify what specific proposals they discussed.

Abiy repeatedly framed the visit as an effort to bring “stability” to Sudan. Abiy’s trip was the first visit by a foreign head of state to Port Sudan since the internationally recognized SAF-backed government relocated there following the outbreak of the war in Khartoum in April 2023.

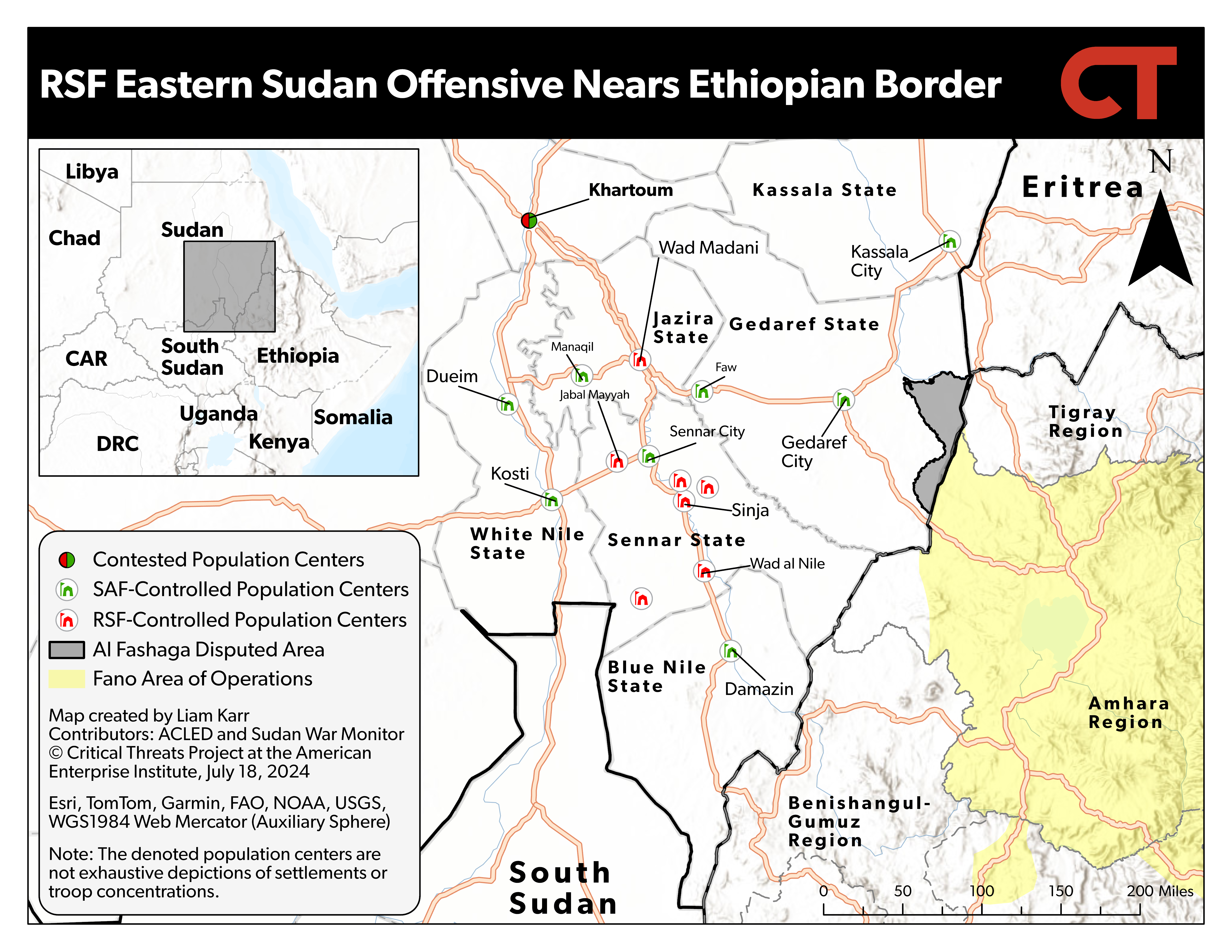

The timing of the visit highlights Ethiopia’s concern that the RSF’s ongoing offensive against the SAF near Sudan’s border with Ethiopia could stoke ethnic tensions in Ethiopia and benefit ethno-nationalist militants that are hostile to the Ethiopian government. Abiy’s visit comes as the paramilitary Sudanese Rapid Support Forces (RSF) have nearly established total control over the crucial population centers in Sennar state—which borders Ethiopia—after launching an offensive in late June. The offensive has caused over 125,000 refugees to flee to areas in Sudan near the Ethiopian border and created a potential RSF presence on its border. The SAF’s last bastion in the state is Sennar city, which the RSF has nearly encircled and begun sieging amid seasonal rains and activity on nearby fronts.

Ethiopian officials are also concerned that the RSF’s growing presence on its border could create opportunities for cooperation between the RSF and Amhara militants—known as Fano—that are fighting the federal government. Fano is a loose collection of decentralized ethno-nationalist militias that claim to protect Amharas, Ethiopia’s second-biggest ethnic group. The rebels base their insurgency on longstanding grievances that the government is persecuting Amharas and that other Ethiopian ethnic groups are dominating the government to marginalize Amharas. Fano fought on the government’s side during the Tigray War but has since returned to fighting the government after a failed demobilization attempt. The militias have been waging a low-level insurgency since federal forces repelled an initial offensive that briefly captured several towns in August 2023.

Fano and the RSF have mutual enemies inside Ethiopia and Sudan. The SAF evicted thousands of Ethiopian farmers in the disputed al Fashaga border zone when it invaded during the Tigray War, most of whom were Amharas who had lived there since the 1990s. The Amhara elite and electorate have since pressured Abiy to respond diplomatically and militarily to Sudan to protect what they view as Amhara territory and have fought in border clashes against SAF forces. The RSF also made unsupported claims that Tigrayan militants are fighting alongside the SAF in Sudan. Fano fought Tigray militants during the Tigray War and is threatening violence if the Ethiopian federal government follows through on plans to repatriate displaced Tigrayans in areas that Fano captured during the Tigray War and has administered since.

Figure 1. RSF Eastern Sudan Offensive Nears Ethiopian Border

Note: The denoted population centers are not exhaustive depictions of settlements or troop concentrations. “CAR” is Central African Republic. “DRC” is Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Note: The denoted population centers are not exhaustive depictions of settlements or troop concentrations. “CAR” is Central African Republic. “DRC” is Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project; Sudan War Monitor.

Greater insecurity near the Ethiopian border benefits Fano even without a formal alliance with the SAF. The influx of weapons and fighting on the Ethiopian border risks a growth in illicit weapon flows into parts of Ethiopia with a Fano presence. An ambivalent RSF or distracted SAF creates opportunities for Fano to take advantage of the vacuum and use Sudan as a rear base. Tigrayan rebels previously used Sudan as a supply corridor and rear base during the Tigray War.

The deteriorating situation on the Ethiopian border also poses various risks to the ongoing peace process in Ethiopia’s Tigray region. The federal government signed a comprehensive peace treaty with the Tigray People’s Liberation Front in 2022 after two years of civil war. The RSF’s claims of Tigrayan rebels in Sudan risk stoking fears that a continued Tigrayan rebel presence in Sudan would allow militants to reconstitute in Sudan and undermine the peace process. The large number of Tigrayan refugees still in Sudan and Tigrayan militants’ historical use of Sudan as a rear base further adds to these concerns.

The potential for ethnic violence against Tigrayan refugees in Sudan also threatens to undermine the peace process. Many of the 80,000 Tigrayan refugees who fled to eastern Sudan have not yet returned to Ethiopia. The RSF’s anti-Tigrayan rhetoric and pattern of ethnic violence indicate that it would attack these refugees. This threat risks causing rapid and uncontrolled refugee flows back into Ethiopia and communal Tigrayan mobilization to defend against RSF abuses, both of which undermine the stability of the fragile and unfulfilled peace process. Many of these refugees are from the same areas where Fano is threatening violence if the Ethiopian government repatriates displaced Tigrayans. The RSF advances in Sennar have isolated the other SAF-controlled areas along the Ethiopian border and set conditions for future offensives that would extend the front on Ethiopia’s border, cause additional refugee flows, and further exacerbate Ethiopia’s various concerns in Amhara and Tigray.

Ethiopia is also well-connected to the other stakeholders in Sudan’s civil war and is trying to advance multilateral, African-led peace initiatives to stabilize the situation. Abiy has forged a relationship with the SAF and RSF since coming to power, in 2018. Abiy helped mediate a transition agreement between Sudan’s various military and civilian parties after Sudanese dictator Omar al Bashir’s fall, in 2019, all of which still play essential roles in the ongoing conflict and potential solution. Abiy continued to maintain these contacts and met with Burhan and RSF head Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo—who goes by Hemedti—several times, including during his last visit to Sudan before the civil war, in January 2023. Abiy hosted Burhan in Addis Ababa in November 2023 shortly followed by Hemedti in December to discuss peace and stability efforts.

Ethiopia’s relationship with Hemedti and his international backers and turbulent relationship with the SAF led news outlets and analysts to label Ethiopia as an RSF supporter. Abiy initially proposed a no-fly zone over Sudan early in Sudan’s civil war in July 2023, which the SAF interpreted as a pro-RSF policy due to the SAF’s air superiority.[28] Ethiopia also has strong ties with the United Arab Emirates (UAE), which is the primary patron of the RSF. The UAE has diplomatically, economically, and militarily supported Abiy since 2018. Various researchers and news outlets have also made unsupported claims that Ethiopia has provided direct support to the RSF, either through arms or rear basing.

Abiy has had a more turbulent but still resilient relationship with Burhan. Burhan took an even stronger position against Ethiopia’s controversial Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam project after taking power following a joint coup with the RSF in October 2021 than Bashir or the civilian-led transitional administration did. This move was partially due to Burhan and the SAF’s strong ties with Egypt, but Egypt and Sudan have concerns about the impact of the Ethiopian dam on their respective segments of the Nile River. Ethiopia and international observers also accused Sudan of allowing Tigrayan rebels to use Sudan as a rear base and transit hub during the Tigray War from 2020 to 2022. Burhan also explicitly went back on his word to Abiy and used the Tigray War to seize the disputed al Fashaga border zone, which has led to sporadic clashes between Ethiopian and Sudanese forces since.[34] The pair discussed these issues during their last meeting in January 2023 before the outbreak of Sudan’s civil war.

Ethiopia has also maintained its relationship with Sudanese civil society and hosts the main Sudanese civilian coalition, Taqaddum. The coalition consists of various aspects of prodemocratic Sudanese society, including political parties, unions, grassroots protest networks known as resistance committees, civil society groups, and pro-democracy rebels. The coalition elected former Sudanese Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok to lead the coalition in May.[38] Hamdok headed the civilian-led transitional government that Abiy helped create before the October 2021 coup.[39] Numerous international leaders, including the Hemedti and US officials, have met with the coalition leaders in Addis Ababa.

Ethiopia has largely attempted to mediate the Sudan’s civil war through multilateral African political forums. Ethiopia initially channeled its efforts through the regional East Africa economic community, the Intergovernmental Grouping of the Horn of Africa (IGAD). However, planned IGAD-led talks collapsed in January 2024 after the RSF and SAF had repeatedly postponed scheduled meetings. The African Union (AU) had supported IGAD’s approach and continued its efforts by appointing Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni in June to attempt to facilitate AU-led talks. London-based Al Sharq al Awsat claimed that Abiy delivered a formal invitation to participate in talks in Kampala with the RSF leader and emphasized the importance of the talks to Burhan.

Other peace efforts led by Egypt, Saudi Arabia, the United States, and the UN have gained minimal traction toward a lasting solution. Egypt led peace talks between various Sudanese political factions including Taqaddum in early July. However, the discussions did not involve the SAF or the RSF, and the SAF-aligned bloc refused to talk to Taqaddum due to Taqaddum’s meeting with Hemedti earlier in 2024.

The UN is holding a shuttle diplomacy summit between high-ranking officials from both sides that began on July 11 to secure a ceasefire that would allow humanitarian aid to enter the country. One of the two sides initially did not arrive on July 11 but has participated in talks since.[47] The UN did not specify which side did not attend.

The United States and Saudi Arabia have also intensified efforts to resume peace talks in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, after their initial efforts collapsed in December 2023. Burhan signaled an openness to reviving the talks after meeting with Saudi officials on July 9. However, Burhan later reiterated his preconditions, and other SAF officials explicitly ruled out resuming Jeddah talks in late May after Burhan talked with US Secretary of State Antony Blinken.

Both factions remain far from common ground on peace talks. Burhan previously showed a willingness to attend such talks on the condition that they be private discussions with Hemedti. Hemedti has advocated the opposite approach and demanded numerous leaders and mediators to be witnesses to any agreements. Burhan has also more recently conditioned negotiations on the RSF withdrawing from civilian infrastructure and homes. Burhan and other high-ranking SAF officials have also repeatedly rejected the idea of peace talks and encouraged soldiers to get “revenge” and fight to the death despite their more receptive language to international partners.

Source: https://understandingwar.org/