Investors, founders feeling more upbeat about Africa’s tech sector

Share

Investors in African startups are increasingly confident of a return to more dealmaking, as the causes of a near two-year pullback by global capital providers stabilize or fade away.

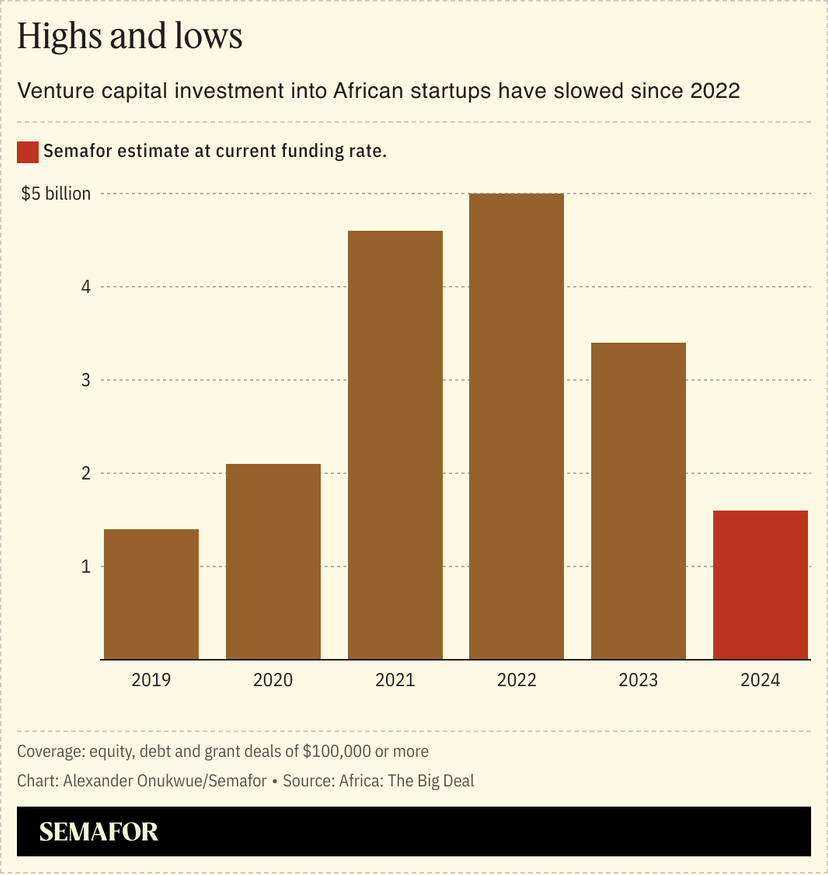

Investments in African startups totaled just $780 million in the first half of this year, down 60% from the same period last year, according to Africa: The Big Deal, which tracks funding data.

And in 2023, African startups raised $2.3 billion from equity deals, less than half the year before, and with a simultaneous halving of the number of investors participating in deals, a report by pan-African investor Partech said.

But signs of macroeconomic stability in Africa’s top destinations for venture capital investment — particularly Nigeria, where the central bank has intervened to calm inflation and currency devaluation — and the prospect of rate cuts by the US Federal Reserve could boost optimism in the funding ecosystem, some investors say.

The last couple of years have provided African tech hubs with lessons on the need for better structure in making investments, to minimize the potential for startup closures and misdeeds, investors say. “There’s much more optimism in July 2024 than if you were speaking to me in July 2023,” Idris Bello of LoftyInc Capital, who splits time between Cairo and Lagos, told Semafor Africa.

“I think we’re seeing this nice plateau where investment capital is coming back in a much healthier ecosystem, with companies that are making real money with real users and a lot less of the froth of the hype cycle,” said Lexi Novitske, general partner at Norrsken22. Her firm participated in a $40 million raise by Tanzania-based remittance startup Nala that closed this month. Norrsken22 will make up to five more African startup investments this year, Novitske said. Similarly, Bello said he expects to see more fundraising deals closed among his firm’s portfolio of startups this year as more funds start to get deployed.

TLcom Capital, a firm that recently secured $154 million for its second African fund, is pursuing the same strategy as before the funding winter. “Our general theory of finding three to five companies that will return our fund has not changed,” its Kenya-based founding partner Maurizio Caio said. His optimism stems from the continent’s need for growth, which invites a role for venture capitalists to “encourage risk and give cash to burn” for entrepreneurs able to create large companies, he said.

Before this funding crunch, African tech benefited from the influx of capital from Western investors who took advantage of low interest rates that made borrowing appealing and encouraged investment. A return to low rates, after a year and half of increases up to last July, could spark capital’s revival on the continent: nearly eight in 10 investors in Africa’s venture capital space in 2022 were international investors, according to the Africa Private Capital Association, an industry trade group.

Alexander’s view

Alexander’s view

The funding crunch has been a necessary growth pain. It has given African tech actors time to test their assumptions under stress. There have been earnest realizations about failed strategies.

An example is Carbon’s decision to stop offering debit cards last month. The Nigerian digital banking startup introduced the cards in 2021 to mark its transition from an app for quick loans to a licensed bank providing a savings account. But between the operation’s dollar-denominated costs and cards not doing much for brand loyalty among customers with multiple bank accounts, the move became a “distraction from the difficulties of going deep and attaining mastery in the other parts of the business,” Carbon co-founder Ngozi Dozie admitted in a post-mortem.

Tesh Mbaabu, a Kenyan entrepreneur, now believes his logistics startup was “completely wrong” for being overly dependent on venture capital while serving a consumer goods industry with slim margins. Marketforce raised $40 million in 2022 for its business of delivering inventory to neighborhood retailers but pushed too far in an aggressive expansion drive modeled after Uber. “Now we know that every dollar a startup can raise is a gift. It should never be the life-blood of the business,” a somber Mbaabu wrote in April.

Caio, whose TLcom is one of the largest Africa-based startup investors by check size, says greater sensitivity to margins will be a mark of the next dealmaking era. “One of the big lessons is that it is more difficult to find high-margin, low-capital intensity business models” in Africa, he told me.

Sparse infrastructure in most countries compels many startups to build multiple aspects of their supply chain themselves at considerable costs. But such potentially high-margin startups exist across industries from Nigeria to Egypt — Caio believes TLcom has invested in at least three of them and that “good” venture capitalists will find more.

The View From Rwanda

The View From Rwanda

The sense of renewed optimism among African investors can be seen in new funds being formed to serve entrepreneurs taking their products to market for the first time. Innovate Africa, a Rwanda-based $2.5 million fund, rolled out this month. It will invest an average of $50,000 in 20 early-stage startups, said Kristin Wilson, the firm’s Ghanaian co-founder and managing partner. The fund will back founders tackling “wicked problems” — widely felt, painful problems whose solutions will cause tremendous change, Wilson explained.

Source: https://www.semafor.com/

You Might also Like